|

AMERICAN

CINEMA PAPERS

2007

|

VENICE 2007

– THE 64TH MOSTRA DEL CINEMA LIFE WITH THE

LIONS by Harlan Kennedy It was madness, music and merriment as the circus came to town. When

the band lining the Lido struck up, there were tears among the cheers. Tears

of loyalty, love and devotion. For we all recognized the tune. “Will you

still need me, will you still feed me?…” Or in the Italian version of the

Beatles lyric, sung by a dozen moved and musical voices in that crowd, “Sara piu bisogno? Sara piu di rogno?” (Literally: “Will there be more need, will there be more dishes of

delicious cooked kidney….?”) Yes, the Venice Film Festival was in its 64th year. It was

also in its 75th, but that figure refers to the date of its birth,

1932. 64 is the number of festivals, in a world and a century so often

interrupted by history, that have actually happened. This event is still a carnival. It still has its travelling acts,

those Hollywood stars who jet in each year to join the mostra

as if it was a dutiful but beautiful part of their workload. Brad Pitt,

George Clooney, Woody Allen, Cate Blanchett, Keira Knightley, Ewan McGregor,

Richard Gere and Bill Murray were among the guests

this year. It still has its clowns jumping through paper hoops (the critics).

Above all, it has its lions and these in turn have their tamers. Marco Muller, chief whipcracker and placer

of head in leonine jaws, was in his fourth and last contractual year as

festival chief. But the bulletin-board voting sheet, stuck up in a sunny

space near the festival café, a sheet on which we could each put a tick

against our listed favourite for 2008 (Jean-Luc Godard

12 votes, Attila the Hun two), had Muller at the top for a renewed tenure. Why not? He has been outstanding. Year after year, he has brought

top-quality meat to be thrown to the lions. This year’s competition programme

seemed almost too tasty. How would we be able to suffer for art – so

necessary for an Anglo-American critic with a puritan conscience – when the

movies were mostly in English and were directed by the likes of Brian De

Palma, Paul Haggis, Kenneth Branagh and Ang Lee? Okay,

Lee’s film was Chinese, and was quickly dubbed BLOKEBACK MOUNTAIN, meaning

the bloke who went to Hollywood was back in his family homeland. But the rest

were treats for the linguistically lazy.

But if our subtitle abilities were underused, horizontal scoping was

demanded and demanding. Our eyes had to dart from side to side constantly in

De Palma’s REDACTED, seeking the telling details, always there amid the

minefields of info in this brilliant Iraq war drama that uses, or replicates,

a mass of multi-format styles. It was the early favourite for Lionisation at

Venice. It is De Palma’s own best film in decades. Video war diaries, blogs, CCTV footage, embedded reporting. The

prolixity of techniques, combined with headlong complexity, rejuvenates this

director’s storytelling flair. Last year at Venice he seemed a man of

stiffening artistry, lost to his inveterate thriller fetishism (THE BLACK

DAHLIA). This year he was the first hot helmer out

of the blocks. REDACTED recounts a rape-and-murder binge by four US squaddies – ravishing a 15-year-old Muslim girl one night

and killing her family – and invites us to see the film as a mid-east version

of CASUALTIES OF WAR. There are no stars, though. And there is no glib unity of perspective.

The chaos of the battlefield is matched by the welter of perceptual

instrumentations which modern technology has offered the outsider as ‘ways

in’ to understanding war. In REDACTED we are never watching, we are always

eavesdropping. We are never witnesses, we are always voyeurs. We understand –

because we are almost sucked into living it – the ease with which decent

youngsters become in every sense demoralised: first robbed of morale, then

mugged of their moral sense. They can no longer tell good from bad in a world

where good and bad actions both are empowered. Stunningly acted by unknowns,

and virtually reinventing the remit of the topical American feature film, De

Palma’s movie made him the comeback kid of Venice 2008. It is far more daring and radical than Paul Haggis’s Iraq-themed IN

THE VALLEY OF ELAH. Not bad as a thriller a thèse

– and better than the preachy pomp of the Oscar-winning CRASH – this

army-base whodunit is about the off-limits killing of an Iraq-returned

soldier. Was he murdered by vicious townies or fellow jarheads? Do we blame

life or the war? Tommy Lee Jones, Charlize Theron and Susan Sarandon are the main cast members

wanting to know. The film is deftly scripted. But after the bold tearing up

of the style-book in REDACTED, it plays a bit like Agatha

Christie meets Aaron A FEW GOOD MEN Sorkin. The US/UK movies flooding the competition in week one also included two Kens and a Clooney. Ken One was

SLEUTH, Kenneth Branagh’s remake of the Shaffer-Mankiewicz thriller, with Michael Caine

trading up into the Olivier role while Jude Law plays Caine’s

old part of the cuckolding intruder in a celebrity writer’s life. Harold

Pinter’s script is pithy. Branagh’s antsy,

multi-angled direction is less so. Ken Two was Loach’s

latest. IT’S A FREE WORLD is another soapbox opera from the Cannes laureate

and fulltime leftist, this time about the exploitation of foreign workers.

It’s a bit same-again, though newcomer Kierstan Wareing, wearing dark-rooted blonde hair that may have

excited the envious admiration of the Golden Lion and his team of coiffeurs,

brings feistiness to the system-combating heroine. And Gorgeous George? No recent

film festival has run its course without a visit from the salt-and-pepper

sexpot. He seems able to replicate himself in every major European city.

MICHAEL CLAYTON, written and directed by Tony Gilroy, who scripted all those

BOURNES from which no braincell returns, is a

dapper law-and-skulguggery thriller. It has about

as much business in a festival competition as a packet of candy in a cordon

bleu meal. But it’s fun. A courtroom setting, and in its fashion a thriller format, distinguish

Nikita Mikhalkov’s 12. Russia’s ex-Venice victor

with URGA (1992) has remade, of all things, 12 ANGRY MEN. (Whatever next? Sokurov’s SERPICO?) But Mikhalkov

cleverly extends Lumet’s jury-room suspenser to two and half hours, sprinkles it with grand

performances (including his own as foreman) and gives each character a

psychologically or sociopolitically charged

confessional scene, so that 12 is as much about a society in the dock –

modern Russia – as about a murder trial and a turnaround among good men and

true. All these movies were academic, anyway, once we had seen LA GRAINE ET

LA MOULET (THE GRAIN AND THE MULLET). Abdellatif Kechiche – the name is a hurricane sneeze – is a

Tunis-born French filmmaker who may be the next big thing in art cinema. His

last movie L’ESQUIVE (GAMES OF LOVE AND CHANCE), which won a suite of French

Cesar awards, was an immigrant love story with the grace of Rohmer and the vitality

of Godard. At Venice the new film, rejected by Cannes when its running time was

three hours, still came in at two and a half. It could be shortened, but so

could WAR AND PEACE. Would it be better shortened? Not

necessarily. Kechiche’s film benefits from the

hammer-blow remorselessness, the boundary-breaking emotional attrition, of

the best scenes in this tale of a French-Muslim patriarch (Habib Boufares), whose

fishing-industry job in a seaside town is threatened and who tries to save

his near and dear by opening a floating couscous restaurant. Might it all go wrong? Might turkeys have a bad time at

Thanksgiving? The writing is on the

wall early and it’s in fluent Franco-Arabic. It says that North Africans are

not welcome in France, unless they can dissolve their identities in the

Gallic gene-and-culture pool. So the stormy clannishness of this big family,

their outward solidarity set off by infighting, marital intrigues and

generational tensions (all vibrantly sketched), is a catalyst for disaster,

waiting to happen. The restaurant’s opening night – a sustained hour of drama and

unravelling – is one of the great scenes of tragicomedy in modern cinema.

Think of VIRIDIANA’s Last Supper and blend it with

the picayune chaos of THE FIREMEN’S BALL. The film’s other ancestor is

Italian neorealism, with a climactic scene

involving the hero-patriarch which breaks the heart even as it wears the

unimpeachable imprimatur of the everyday. Wonderful performances enrich the deeply-worked script and story. The

old man’s ex-wife (Bouraouia Marzouk)

is a Mother Earth who still cooks the extended family’s feasts, her couscous

a secret weapon – or not so secret – in ensuring nuclear togetherness.

The old man’s new partner (Hatika Karaoui) is an ageing sorceress whose nubile, hotheaded daughter (Farima Benkhetache), outwardly rebellious if inwardly loyal,

saves the day, or nearly, by bringing a gust of native culture into the

banquet. Belly dancing! This shindig, obsequiously sown with invited bigwigs

and provincial Chauvelins, has the doom of

multi-ethnic appeasement upon it. Yet Kechiche’s

characters come close to making the impossible work, to making one jealously

insular ancien regime, France, extend the hand of welcome to another, even older, even wiser

in the tribal schisms of the human spirit. When fiction becomes too frightening – because it amplifies truth into

the epiphanic – filmgoers can always retreat into

fact. Is there anything more comforting than a biopic? It wraps us like a

warm blanket. We’re cosy in the confines of the known, the particular, the

unchanging. So, conversely, the bold filmmaker knows that to make a biopic grabby

and surprising he must put everything back the opposite way. He must dose his

movie with seeming fiction. He must bring back lies and order up truant

fantasy. In Todd Haynes’s Bob Dylan celebration, I’M NOT THERE, he must

entrust the role of the folkie to six different actors, each playing a

different essence. Will the real Dylan please stand up and walk towards us on twelve

legs? The balladeer-arthropod is duly enacted by Haynes’s half-dozen.

Christian Bale, Heath Ledger and Richard Gere are starrily among them, but the winning mimic is Cate Blanchett, who not only

has Dylan’s features (wolfish cheeks, hooded eyes) but seems to have spent a

lifetime studying his body language. Everything is perfect, from the

hunch-shouldered self-compression of the introverted Dylan, a human tortoise

repelling world and media intrusion, to the snaky sidewindings

of the celebrity who knew how to have a funky time slipping through adoring

crowds or sidestepping paparazzi. I’M NOT THERE, though, is more than serial mimicry. It bids to suggest

that instead of a simple integer an artist is the sum of many parts, some of

them incarnations of the new, some of them pre-existences that shaped their

successor as seasons shape landscapes. So Richard Gere

plays Billy the Kid, a Dylan idol and in Peckinpah’s

PAT GARRETT AND BILLY THE KID a screen companion to Dylan the actor. Marcus

Carl Franklin plays the boy Woody Guthrie, a train-hopping mini-hobo bringing

the spirit of country-and-southern to the underprivileged north. And as if to

prove that life imitates art – or that critics can be unwittingly infected by

a film’s mischief-making – on the outer fringes of the film’s dramatis

personae dwells Julianne Moore’s hilariously well-observed Joan Baez, a role

enacted, according to one reviewer of a prestigious newspaper, by ‘Marianne

Moore’. Ah the past and its bards and visionaries! How can we escape them?

Why should we want to? Filmmaker Peter Greenaway cannot escape

Rembrandt van Rijn. The British bricoleur is almost

an honorary Dutchman – he has lived in the Netherlands, his producer comes

from there – and northern European painting has been an obsession. NIGHTWATCHING

is a Rembrandt biopic with a difference, indeed with about a hundred.

Westerners weaned on the Alexander Korda flick, in

which Charles Laughton played the painter as a mad

overgrown baby with a visionary gleam, will take a while to adjust to Martin

Freeman. A sitcom actor (THE OFFICE) and minor film player (HOT FUZZ, THE

HITCHHIKER’S GUIDE TO THE GALAXY), he seems lightweight for the role. For an

hour he plays Rembrandt as a stand-up schismatic, scattering dissent and

iconoclasm under the guise of proletarian good cheer. He isn’t far from being

Tony Hancock in a Netherlands version of THE REBEL. Then it gets deeper and darker. Rembrandt paints ‘The Night Watch’,

his scandalising group portrait of local dignitaries playing at being

home-guard heroes, the ridiculous posing as the sublime. In the process he

exposes a possible murder plot. The sky falls in on him. He loses money. He

is unhappy in love: his wife Saskia (Eva Birthistle) dies and his remaining passions settle on his

servants (Jodhi May as Geertje, Emily Holmes as Hendrickje). He is beaten up and nearly blinded. Greenaway

– we can’t help feeling – loads the tragic dice: Rembrandt did, after all,

keep painting and making masterpieces. But the sturm

und drang allow Freeman to re-colour his performance

with swirling emotional hues, to deliver well-scripted speeches and to

present a portrait of the artist as riven martyr. NIGHTWATCHING is his best film since THE PILLOW BOOK. It reminds us

that this British director is still a formidable artistic energy-flow for

whom the world – he included – seems

unable always to fight the right channels. Here the artful sets, magisterial

lighting and densely written dialogue all raise this painterly biopic to a

higher level than the usual dauber’s progress. And they hoist exalted and

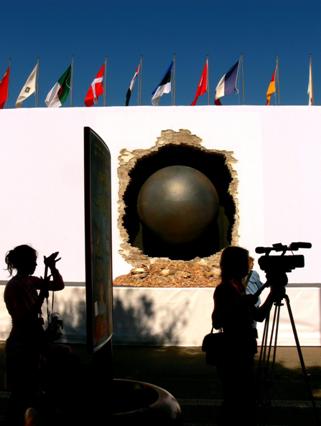

exalting questions about art’s place in society and society’s place in art. The Mostra’s place in Lido life, during two

weeks in September, is indisputable and unavoidable. There was a diaspora of lions this year. The gold-painted jungle cats

fashioned by Italian movie designer Dante Ferretti,

which stood in serried pride outside the Palazzo del Cinema during the last

two years, were now scattered all over the island, or those parts near the

cinemas. You could be eating a sandwich and casually lean one arm on

something convenient – it turned out to be a lion’s snout. You could say

“Sorry” to a figure you accidentally bumped into on your way into the

festival palace – it would be a lion. A friend had an entire conversation

with a supposed human interlocutor, on a dark evening after a movie, and it

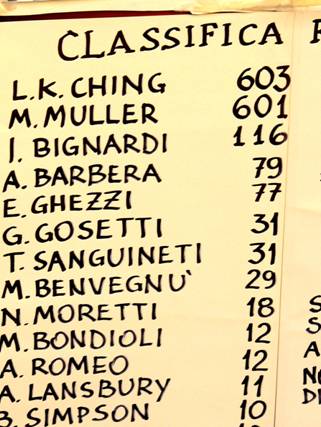

was a lion. There was another widely enjoyed eccentricity this year. Who or what

is LK Ching? In that poster-sheet poll for next

year’s festival director, a poll whose latest vote numbers were diligently

scrawled each day in bold black ink, Marco Muller remained neck and neck with

the said Ching – whom absolutely no one had heard

of. By festival’s end, the magnificently unknown Ching

had actually overtaken Herr Muller, though theories abound that Muller has a

Chinese passport and alias and was himself ‘Ching.’

I don’t believe this. I no more believe it than that a Sinophile conspiracy existed to ensure, through the

presence of Zhang Yimou as jury president, that for

the third year running at Venice a director of Chinese origin won the Golden

Lion for best film. After Ang Lee in 2005

(BROKEBACK MOUNTAIN) and Jia Zhang-ke in 2006 (STILL LIFE), it was Lee again who strode to

the platform to collect the gong for LUST, CAUTION. He is starting to become known as Gong Lee. Born and raised in Taiwan,

and lifted to international fame in Hollywood, Lee comes from Mainland

Chinese parents and returned to China for his new film. It was a shock to

supporters of the tipsters’ favourites

– THE GRAIN AND THE MULLET, REDACTED, I’M NOT THERE – that the jury

picked this jewelled, erotic, but sometimes oddly novelettish

espionage epic. Newcomer Tang Wei plays a Shanghai

Mata Hari, a theatre student who offers herself as

bait in a resistance gang’s attempt to entrap and assassinate a Chinese

collaborator with occupying Japan. He is played by Sino-superstar Tony Leung

with a slicked back hairstyle, smouldering charm and eye-whacking period

suits. When he wears them, that is. In the sex scenes the film does not so

much smoulder as threaten intercontinental conflagration. Tang and Tony go to

it with a will, without a stitch of clothing, in positions not approved by

the World Missionary Society. There are prolific hints of S-and-M. The

shocked American authorities have already delivered an NC17 rating. Ang Lee, blithely throwing fuel on the publicity flames,

hinted that the sex scenes were performed by the actors for real. It was not the only surprise prize. Amid a roar of polite incredulity,

Brad Pitt won Best Actor for doing nothing much – though his petitpoint work with face and voice can be underestimated

– in the main role of Andrew Dominik’s THE

ASSASSINATION OF JESSE JAMES BY THE COWARD ROBERT FORD. Pitt is alluringly grizzled and ironic,

over the two-and-a-half-hour story, as he teases his ex-cronies into

preparing for him the immortalising execution, the mythopoeic

quietus, that he knows is only a matter of time. Cate

Blanchett’s silver goblet for Best Actress was well

deserved. So were Brian De Palma’s Best Director Silver Lion for REDACTED and

the split Special Jury Prize honouring I’M NOT THERE and THE GRAIN AND THE

MULLET. Nothing became the Venice Film Festival better than its leave-taking. We

who watched the awards show will remember the strangest sight and sound of

all. A frail Catherine Breillat, the jury member

chosen to come to stage-front to present Abdellatif

Kechiche with his guerdon, chose, all of a sudden,

to engage the Frenchman in an extended dialogue about the film’s meaning and

symbolism. At the back of the stage an aghast lineup of

emcees, VIPs and dolly-bird hostesses stood about, politeness preventing

intervention during these minutes in which the night’s vacuous words of congratulation

were replaced by dense engagement with a movie’s actuality. Breillat was finally coaxed back to sanity. Kechiche was urged towards the photographers. A moment of

content had disturbed the form, a scintilla of substance had short-circuited,

almost, the show. Now it could go on. And it will. And it should. And we love it, in folly as well as in

fulfilment. Floreat la Mostra. Book my gondola for 2008. LK Ching (all rights reserved). COURTESY T.P. MOVIE NEWS. WITH THANKS TO THE

AMERICAN FILM INSTITUTE FOR THEIR CONTINUING INTEREST IN WORLD CINEMA. ©HARLAN

KENNEDY. All rights reserved |

|