|

. |

|||

|

AMERICAN CINEMA PAPERS

2013

CANNES 2013 – THE NUTTY PROFESSION

CANNES 2013 – PICTURES FROM HELL

|

CANNES –

2013 THE 66TH INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL THE BIG BLUE by

Harlan Kennedy

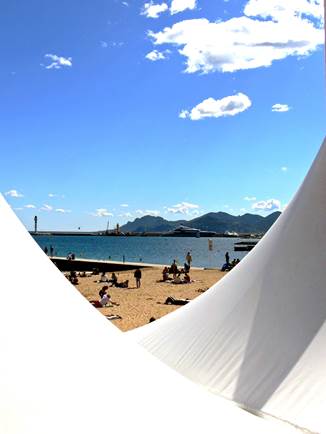

Man was born free and everywhere he is in Cannes, or on the way there. Each year he treks, trucks, trains, planes. Each May the little fishing town on the Azure Coast fills to bursting, depopulating the rest of the planet. Never mind rain, storm or million-dollar jewel robbery (we had all those). This place is still one of the people magnets of the globe. Who can complain? We regulars still adore the pull of the place, the captivation and coercion. As one Dylan (the poet Thomas) said, we sing in our chains like the sea. Another Dylan, the balladeer Bob, happened to be the patron saint of the film that caused most cheer at Cannes 2013. The Coens’ INSIDE LLEWYN DAVIS celebrates a cultural phenomenon that – just like this film festival – had its establishing heyday over half a century ago. Today, like Cannes, it still rattles those gilded chains which began as a golden umbilical cord. Back in the 1950s/early 1960s the New York folk-singing scene – leading up to Bob Dylan, who appears in the movie’s final act – was as momentous an infant as the then young Cannes. The era is celebrated by the makers of BARTON FINK and O BROTHER WHERE ARE THOU? with the same libating cocktail of influences as those films. Homer and James Joyce. A ‘Ulysses’ motif extends from the name of the central cat – a ginger tom adventitiously adopted by the penniless Greenwich Village folk singer of the title (Oscar Isaac) after he shuts the door, departing, on a crash pad from which the feline has uninvitedly issued – to the day-in-the-life structure which (though, okay, it’s more than a day) confers Odyssean circularity and homewardness on a story that ends as it begins. The Coens make struggle and failure spellbinding. Llewyn Davis isn’t going to be a star. (He is slimly based on Dave Van Ronk, who wrote about the early New York folk scene in THE MAYOR OF MACDOUGAL STREET). But his misadventures are funny – girlfriends forming an orderly queue at the abortionist’s, gigs that spiral from dysfunction to disaster – and later take on a gothic-seriocomic tinge typical of the Coens. John Goodman has a terrific cameo as a sinister-funny aging balladeer, a creep-you-out version of Burl Ives, whose chauffeured car scoops up the hero during a snowy, nocturnal sashay from Chicago, where the hero has failed to impress super-agent F. Murray Abraham. “I don’t see a lot of money here,” Abraham intones after hearing Davis sing a melodious but non-contempo ditty about Henry VIII and Jane Seymour. I’m not sure I see a lot of box office in INSIDE LLEWYN DAVIS. But it is surely heading for a cherished life as a cult classic. Lost generations. That was a big theme at Cannes, beginning with the lost-est of all: that of F Scott Fitzgerald and his peers, mythically characterised by the author of THE GREAT GATSBY. Baz Luhrmann’s festival opener, ra-ra’d by some, raspberried by others, also had Carey Mulligan in common with the Coens’ film. This English actress is now so at home in her adoptive America. If she couldn’t quite get the measure of GATSBY’s Daisy – what actress can, with that voice “full of money” (whatever Fitzgerald’s wonder-line means) and that switchbacking between sweetness and betrayal? – she is superb for the Coens where, briefly, she sings fit to bust a heart, as she also did in SHAME. Lost generations. Sometimes a generation close to you is ‘lost’: such as your own children. In bizarre succession several films at Cannes portrayed parents losing touch with – or control over – their kids. Francois Ozon’s JEUNE & JOLIE (YOUNG & BEAUTIFUL), Asgar Farhadi’s LE PASSE (THE PAST) and Hirokazu Kore-eda’s LIKE FATHER, LIKE SON are all skilled chamber dramas, scanning in on family life at the point where, like a vase, a beautiful construct is showing its first hairline cracks. How good Ozon is when he’s not doing glee club kitsch. (Who can prefer 8 WOMEN to SWIMMING POOL?). In YOUNG AND BEAUTIFUL he’s right on the money in tone and craft with the tale of teenage girl Isabelle (Marine Vacth) losing her virginity – with ominous nonchalance – on a vacation, then moonlighting from her Sorbonne studentship to sell her youth and pulchritude as a prostitute. BELLE DU JOUR alarm bells? It would be a shocking tale if Ozon had decided to direct it for shock effect. Instead we move matter-of-factly through the internet date arrangements and hotel trysts: sex, even paid sex, has a new market place today, a new glibness of transaction, thanks to the net. (Thank you, thank you). The girl’s mother, discovering all, is left floundering in the backwash. Indignation won’t do; the girl herself, is too cool and self-collected. It will all come right finally, with help from Ozon’s favourite dea ex machina, Charlotte Rampling, in a clever, watch-and-see finale. Iran’s Asgar Farhadi won Best Foreign Film Oscar last year for a SEPARATION. In THE PAST he and actor Ali Mosaffa skip to Paris for a more subtly European tale of fractured relationships. As in Ozon’s film a daughter (Pauline Burlet) is the centre of the storm, here reacting to the follies of her elders. French mum Berenice Bejo (THE ARTIST’s comedy moll skilfully sequencing into serious drama) is finalising her divorce from Mosaffa to marry an Arab-French toyboy (Tahar Rahim of A PROPHET). The girl looks on at what she sees as the vandalisation of her childhood and its sense of belonging: emblemised by the ramshackle home near a railway – transience in, as it were, the house’s DNA – whose rooms are undergoing daily, messy makeover. The tone is funky-Chekhovian and for 90 minutes moving and astringent. The only, late spoliation: a weakness for melodramatic complications that include a vengeful email correspondence and a coma victim used (not for the first time in cinema) for cataclysmic plot engineering. Jury president Steven Spielberg, in a rare off-leash moment early in the festival, voiced his admiration for Japan’s LIKE FATHER, LIKE SON. No surprise: it’s about kids, with a pile-high-the-sweetness-and-pathos plot. A rich architect and wife are told they’ve brought up the wrong son. Their 6-year-old is not biologically theirs; the tot was swapped with another at birth. A Spielberg accolade is not a shoo-in blessing – people might see a wall of kiddy-centric sentimentality moving towards them. But Hirokazu Kore-eda (AFTER LIFE, I WISH) doesn’t do schmaltz. He does observation incandescent with detail. The story is laid out in masterly stages, with the second set of parents – a down-at-heel appliance shop owner and wife, who have raised the architect’s blood child – characterised as meticulously as the first set. The nature-nurture debate itself is given its due dialectical measure. How many years of loving, or more exactly how few, does it take before parenting starts to count more than parentage? There are no rules in relationships. When there are, time rips them up. Midway through the Cannes Film Festival, that sacred wedding of art and commerce that has lasted 70 years, a rival form of nuptial contract underwent a French revolution. Gay marriage was legalised. In a trice, as if awaiting its cue, BEHIND THE CANDELABRA leaped into Theatre Lumiere. Steven Soderbergh’s Liberace biopic reminds us how far western society has advanced since a famous mink-wearing, toupee’d, ring-festooned Las Vegas entertainer had to spend his last days pretending he wasn’t gay, let alone a casualty of the Aids virus. Michael Douglas and Matt Damon play ‘Lee’ and lover Scott Thorson, whose memoirs inspired the script, and if the wacky-casting connoisseurs come to goggle Douglas – laudably at home with the grins, queenly bons mots and bouffant wigs – they will stay to admire Damon, no less a super-trouper as the gay Adonis with flights of foot-stamping fret and fury. The other big same-sex love story at Cannes, and instant Golden Palm favourite, was Abdellatif Kechiche’s BLUE IS THE WARMEST COLOUR. That’s the UK/US title for LA VIE D’ADELE CHAPITRE 1 ET 2. With a lesser movie you’d be exhausted by the rolling-stock title before the opening scene. Explanation for it: Kechiche, adapting Julie Maroh’s graphic novel LE BLEU EST UN COULEUR CHAUD, has changed the heroine Celestine’s name to that of his teenage newcomer-star Adele Exarchopoulos (more syllables for the space-challenged marquees) and, since the film dwells obsessively on its girl protagonist and her every word, gesture, nuance, facial expression, has incorporated her name in the title Did someone say ‘graphic novel’? As a graphic movie BLUE/ADELE just about set the Croisette on fire. The love scenes between school-age Adele and slightly older Emma (Lea Seydoux) – tomboy art student and painter with blue eyes and matching hair, met in an AC/DC Paris bar – are as corblimey/incendiary as any outside a blue movie. (Can’t get away from that colour). Two voluptuously unclothed girls wrestle for minutes on end, exploring every nook of each other’s nooky-intensive anatomy and every cranny of each other’s gasping, gymnastic libidos. The ‘sex’, though, isn’t half the story. The Tunisian-born French director of COUSCOUS (LA GRAINE ET LA MULET, 2007), that intimist epic that showcased Kechiche’s empathy with young women characters and his revelatory skill with close-up camerawork, knows how to convey those tremulous nuances understood in the phrase ‘falling in love’. After an hour of watching Exarchopoulos talking, thinking, reacting, interacting in everyday chat – those schoolyard symposia about everything from sex to Sartre, from rock to Racine – we watch, with Adele and Emma, the titration of intellectual kinship into the elemental, chemical compatibility of sexual attraction. The improvised dialogue; the tics and flickers of facial response; the eyes that make and mirror each other’s telltale fires. It’s astonishing filmmaking, so close to reality, in shots of faces intimate enough to explore every grain and pore of skin, that we can seldom perceive the invisible border between fiction and life. 187 minutes long, the film also has time to build a society around its central couple. A Rohmerian wry detailing is invested in the friends, parents, fellow students and artists. One mum and dad, Emma’s liberated bohemians, welcome the lovers into their home. Adele’s parents aren’t expected to be so tolerant. “It’s good of you to help Adele with her philosophy,” they lob well-meaningly at Emma across the dinner table, a few hours before the girls are upstairs in bed, desperately stifling their naked cries of joy. The almost inevitable breakup comes; a carnal carnival turning to a marche funebre. Even here, Kechiche insists on time to present the meteorology of grief; to deconstruct/reconstruct the stages of disenchantment; to chart the climatic progressions of unhappiness; to score the canonic harmony of romantic loss, whereby one lover is always a bar or more ahead of, or behind, the cruel music of the other’s cooling heart. Adele Exarchopoulos gives an astonishing performance – ‘Cannes Best Actress’ (we thought) glowing through every word and moment – though performance seems the wrong term here, as it does for almost everything in Kechiche’s incandescently truthful filmmaking. Three hours of BLUE IS THE WARMEST COLOUR and you had forgotten, at Cannes, that blue was the absent colour. This year, on the so-named Cote d’Azur. For a week we were flung along seafronts by winds and horizontal rainstorms. The Cannes fireworks display lasted ten minutes, then was drenched into an early death. From destroyed umbrellas wrought into shapes worthy of Dali or Duchamp, you could have compiled an art installation the size of the Carlton. Then sold it for a fortune. All good fun

if you like being forced into cinemas – where else to go without drowning? – to see films out of which you might otherwise have fled or

Things started getting cheery, or cheerier, in the festival’s second week. Cannes is the only town where the sun and stars come out at the same time. A seeming cloth of gold is laid the length of the Croisette by day, courtesy of a cloudless Mediterranean sky. The Croisette is still light, still golden, as the first heavenly bodies start being decanted from the limos. Place, base of the red-carpeted Palais steps; time, sixish. People: the likes of Michael Douglas, Matt Damon, Sharon Stone, Robert Redford, Roman Polanski, Marion Cotillard, Leonardo DiCaprio, Uncle Bruce Dern and all. Old actors never die. They just get teleported to Cannes, from that twin town for retirees Beverly Hills (it really is twinned with Cannes), to accompany a comeback flick or collect a career accolade. Dern stars in Alexander Payne’s latest, NEBRASKA, a kind of old coots’ reunion – let’s be frank – in black and white, from the maker of ABOUT SCHMIDT and SIDEWAYS. Dern, a rodent-featured star who once set traps for his fans with the likes of SILENT RUNNING, THE KING OF MARVIN GARDENS and COMING HOME, is superb as the addled but endearing Montana paterfamilias straying into a neighbour state to revisit past haunts and re-bond with a son. His family has a longstanding feud with another screen veteran, Stacy Keach. Once the screen’s reigning master of gloom, doom and portent – FAT CITY, LUTHER – Keach is first seen singing in a small town Karaoke bar. It’s like discovering Madame Defarge unexpectedly hosting a provincial knitting bee. Other oldies

and goldies at Cannes 2013 included Jerry Lewis and

Kim Novak. (**see separate feature**). Festival director Thierry Fremaux strove to keep the balance of ages. To

counterweigh the old crocks, he drafted in James Franco, heart throb

actor-auteur, for western cinephiles, and Guillaume

Canet, another heartthrob To the

question, “Why don’t actors just act?” there are several upbeat answers,

ancient and modern. The Cannes Classics sideshow, rich this year, showcased directors-and-sometime-performers

Jacques Demy (LES PARAPLUIES DE CHERBOURG) and Jean Cocteau (LA BELLE ET LA

BETE). Dutchman Alex Van Warmerdam has an

entertaining extended cameo in his BORGMAN, an antic home-invasion comedy in

which the invaders just might be from another The great Polanski once played Mozart on the Paris stage in AMADEUS and there is something oddly similar about this confection. VENUS IN FUR takes the notional artistic mastery and expertise of one character – Amalric, taking the ‘Salieri’ role, as the author-director of a stage version of Leopold Sacher-Masoch’s infamous 1870 novel pioneering the concept of sado-masochism – and allows that mastery and expertise to be blown away by the gift of arrogant instinct and intuition. Seigner, never better, plays the auditioning actress, seemingly uncouth and untutored, who manifests a more probing understanding of the source text. Soon she is dancing artistic and innovating rings around her partner. Polanski’s second successive stage adaptation, after the bright and barbed CARNAGE, is a funny, clever caprice. Think of BORN YESTERDAY, splice in AMADEUS and work the final design into a Pirandellian party piece. Came the hour, came the prizes. BLUE IS THE WARMEST COLOUR, which in any potlatch of puritans or diner de neo-cons would be ruled out as too close to porn for a Golden Palm, won, yes, the Golden Palm. It’s France, isn’t it? If they can be the first country in frontline Europe to legalise gay weddings, they can – and should and will – be the first to legitimise graphic Sapphic cinema. Adele Exarchopoulos should have won Best Actress. But Berenice Bejo, the un-gonged darling of Cannes in the year of THE ARTIST, was compensated this year, rewarded for her seamless transition to straight dramatic acting in Asgar Farhadi’s THE PAST. And durn it, Bruce Dern won Best Actor for his seraphic non-acting in NEBRASKA. Collecting the guerdon he beamed with a smile that said, ‘I can show you Heaven in a grain of underacted gratitude.’ Actor Oscar

Isaac, on the Coens’ behalf, accepted with no less

grace the second-place Special Jury Prize for INSIDE LLEWYN DAVIS. The Coens paid the price for artistic integrity.

Gimmick-free, hyperbole-free, ostentation-free – in short a quantum advance

on the look-at-me-I’m-so-darlingly-nutty BARTON

FINK (which swept To prove the point, violent movies collared the other big prizes. Mexico’s Amat Escalante took Best Director for HELI, a ripping, snorting, gun-crazy yarn about a 12-year-old girl and a lovestruck police cadet. And China’s Jia Zhang-ke took Best Screenplay for the blood-bespattered A TOUCH OF SIN (see above). It just goes to show. You can’t have kiss-kiss (BLUE IS THE WARMEST COLOUR) without bang-bang. What is it the feller, or rather the Fuller (Sam), said? “Cinema is a battleground. Love. Hate. Action. Violence. Death. In a word…. emotion.” Right on the money. It took a canonic French director, mind you, Jean-Luc Godard in PIERROT LE FOU, to get a canonic American director to say this on camera. But the words are true for all times, all countries – and all festivals. Love. Hate. Action. Passion. Entertainment. Art. In a word….Cannes. COURTESY T.P. MOVIE NEWS. WITH THANKS TO THE AMERICAN FILM INSTITUTE FOR THEIR CONTINUING INTEREST IN WORLD CINEMA. ©HARLAN

KENNEDY. All rights reserved |

|

|

|

|

|

||