|

AMERICAN

CINEMA PAPERS

2005

|

BERLIN FILM FESTIVAL – 2005 EVENT HORIZONS 55th INTERNATIONALE FILMFESTSPIELE – BERLIN by Harlan Kennedy Timeline Berlin. I jetted into Berlin on a snowy night in St.

Valentine’s week. The trading floor of world cinema moves here every

February. The German capital is the only place in the world where a ‘bearish

market’ is good news. Filmmakers compete for the animals with a passion

directed elsewhere only at Italian lions and French palmfronds. My mission was to witness and chronicle a unique exchange of valuables

between east and west. A movie epic from Moscow was being introduced to westerners prior to

friendly extradition to a top Hollywood studio. (“You are now leaving the

Russian sector”). Nearby an Anglo-American directing genius was having his

life showcased to easterners prior to a trip round the world. (“You are now

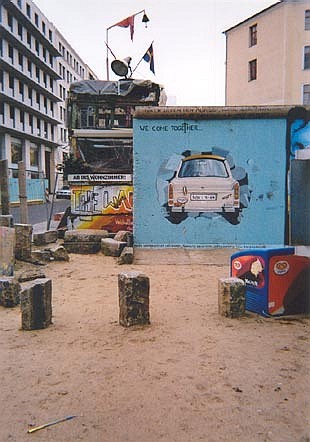

leaving the British and American sectors.”) All this was within the square mile of Berlin heartland known as the Potsdamer Platz, where history

was made and unmade 60 years ago when conflict and division died – for a

generation at least – in a death-doomed dictator’s bunker. It was a night for turned-up collars. Snow lanced diagonally from inkblack skies. Ice-gusts bit the tops of the ears. The

wind almost whipped me into the festival palace for the midnight showing of Sergei Lukyanenko’s NIGHT WATCH

(NOCHNOJ DOZOR), playing to an audience of wakeful night-creatures whose

antennae twitched with excitement at encountering a movie that had been so

successful in its native Moscow that it was now being been bought up for

remake and franchising by 20th Century Fox. “Never before has a film opened as

successfully in Russia as did the fantasy thriller by advert director Timur Bekmambetov,” reported

the top German newspaper Die Welt. Among the films NIGHT WATCH had punished

or outdistanced at the box office were THE MATRIX, TROY, STAR WARS and THE

LORD OF THE RINGS. Bekmambetov

is a Kazakhstan-born 44-year-old, educated in film in Moscow. His second

feature THE ARENA was co-produced by Roger Corman,

not previously noted for forwarding the careers of Kazakhstanis.

Corman must have noted that Bekmambetov

had a particular kind of insanity, the kind that one calls genius. Genius as

a storyteller and pop imagist. NIGHT WATCH, based on the first volume of a sci-fi trilogy by Russian

author Sergei Lukianko

(who co-wrote the screenplay), does everything that Hollywood does and does

it – if not better – then with a passion, a primitive power and a troubled

ferocity that could only come from a land far from Tinseltown,

from a land where Europe eyeballs Asia across cold and rugged remotenesses. The plot? You could call it the usual metaphysical mayhem. A world

divided between good and evil, light and dark. Team leaders with funny names:

Geser, the white wizard and head of the ‘Night

Watch’ (which monitors the forces of evil), and Savulon,

the dark wizard and leader of the ‘Day Watch’ (which tries to outmanoeuvre

the forces of light). And in center-screen the hero

Anton (Konstantin Khabensky),

who discovers that he is a chosen one, a magically-powered wizard working –

he thinks – for the good guys. What makes a difference here, in a world concussed by MATRIXES and

mowed down by CONSTANTINES, is the devout and maniacal manner of it all. Bekmambetov has surely learned his gangbusting

style and storytelling techniques from the great Russians, from the assaultive logorrhea of

Dostoevsky, from the apocalyptic melismas of

Mussorgsky, from Eisenstein’s kinetic human figurations like molten

sculpture. You have to gasp delightedly at such surreal participants as the good

wizard Geser, who performs barehanded unanaesthetized surgery on wounded heroes, Olga the owl,

who turns into Olga the beautiful nude, shaking herself feather-free as Leda

must have done after being raped by swan-disguised Zeus. (We are a long way

from Harry Potter). And there is a searing gothic panache to the visuals, to

images like the ancient viaduct between stormcloud-girt

mountains on which the ultimate battle is fought, though we soon realise that

the ultimate battle – which comes in scene one – is merely a prelude to more

ultimate battles to come. There can be few better definitions of ‘world cinema’ than a European

film from an Asian-born director which is greedily co-opted by America. But

one definition as good is a director, now departed, whose dozen films and

half-dozen ‘almost-films’ roamed across cultures, continents and epochs with

a breadth and intellectual inquisitiveness unmatched since – well, in movie

history, simply unmatched. It is Stanley Kubrick. The Berlin exhibit

devoted to his work was housed in the Martin-Gropius-Bau,

a lone monument of early 20th century German baroque sitting in

the snowbound modernism of the city’s restored and ever-rising centre. Kubrick

would have loved this setting. It is like the Augustan Age bedroom

mysteriously sited on Jupiter in 2001. Or like that Rossini music chirruping

away in the futurist Dystopia of A CLOCKWORK ORANGE. Huge seated statues,

time-eroded and without their heads, do sentry duty on either side of the

museum’s front steps. Then you rise to the second floor to enter the

time-mazes of the Stanley Show itself, a winding labyrinth as intricate and

magical as the maze in THE SHINING. Each film, plus its history, gets a room or two. There are cameras,

costumes, curios, correspondence and Kubrick quotes

inscribed on walls. (“I’ve got a peculiar weakness for criminals and artists

– neither takes life as it is. Any tragic story has to be in conflict with

things as they are”.) His films, you realise, were all about war. Public wars in PATHS OF

GLORY, SPARTACUS, DR STRANGELOVE, BARRY LYNDON and FULL METAL JACKET. Private

wars, enacting the eternal tension between bonds of feeling and boundaries of

selfhood and identity in human relationships (LOLITA, THE SHINING, EYES WIDE

SHUT). And civil or civic wars in those films where the outlaw tribe declares

war on society by transgression or rebellion

(THE KILLING, A CLOCKWORK ORANGE). The films-that-never-were get as much space in this show as the movies

that were, are and always will be. NAPOLEON would surely have been Kubrick’s magnum opus. He completed the script, scouted

the locations and even invited Oskar Werner to play

Bonaparte. In the Berlin exhibit we see their exchange of letters. Kubrick’s polite and spidery scrawl offers a meeting in

London to talk turkey – and Russia, Belgium, Italy and other cynosures of the

French empire-builder’s eye! Werner agrees to the meeting but points out –

fatefully? Even fatally? – that another Napoleon epic was then in the

pipeline, the Sergei Bondarchuk-Rod

Steiger collaboration, the film that eventually,

persuaded Kubrick to abandon his project. Then, among aborted movie dreams, there was ARYAN PAPERS. More

sketches, more costumes, more books; a shooting schedule; a cast; and in one

room of this show an entire wall of filing drawers labelled “Vehicles, “Arms,

“Clothes” etc. This would have been Kubrick’s

SCHINDLER’S LIST. But it was news of Spielberg’s own swiftly advancing

Nazi-era project that cancelled Stanley’s. Is there a little bitterness in

the Kubrick summation of the Schindler story –

another graffito on the exhibit’s walls? “That was about success, wasn’t it?”

he tartly comments. “The Holocaust is about 6 million people who get killed. SCHINDLER’S

LIST was about 600 who don’t.” Not a man to hold a grudge? Kubrick’s last

lost dream, his final surrender of a fully-researched work of cinema, was AI.

And Spielberg was the beneficiary. We see from 40-odd full-blown sketches and

designs how wonderful Kubrick’s AI might have been.

We know too well how wonderful Spielberg’s wasn’t. Did the director of 2001:

A SPACE ODYSSEY really think that the waning Hollywood starchild

whose powers had weakened steadily from the visionary karma of CLOSE ENCOUNTERS

OF THE THIRD KIND to the Disneysaurs of JURASSIC

PARK was up to the job? But by late career, how many jobs was Kubrick

up to? Walking whole decades as we pass from one room to another in this

show, we realise that the director’s vision, even while initiating his

projects, was so painstaking, so perfectionist, so time-costly that he fell

behind on a macrochronological level. He began to

be entire epochs behind the time.

Too late for a screen Napoleon. Too late for screen Nazism. Too late for AI’s

futurist nirvana, in a movieworld clotted with

whimsical clairvoyance and high-cost sci-fi fantasy. Yet in earlier times Kubrick was the great

pacesetter. Everyone lagged behind him.

2001 is celebrated in this show by a front-projection display room, proving that

Stanley’s own technical innovations made the ‘apes’ in the desert possible,

made them seem as if they really were prancing about in a primeval wildness

rather than in Shepperton Studios, England, in a

maze of cameras, mirrors and reflectors. And DR STRANGELOVE. What a leap into the future that was. Not just in

its enactment of nuclear paranoia but in the challenge to audiences of its

compound, multiphonic tone. Tragedy, comedy,

slapstick, mockudrama: all present and incorrect –

by Aristotelian standards of unity! – and all functioning like perfectly

primed engines in a devilish flying machine. It is touching, even a little

awesome, to see the first scribbled ideas for the film’s title jotted by Kubrick on the blank forepage

of a screenplay. “DR DOOMSDAY”. “MY BOMB, YOUR BOMB”. “DON’T KNOCK THE BOMB.” “THE PASSION OF DR

STRANGELOVE”. “DR STRANGELOVE’S SECRET USES OF URANUS” (not pronounced,

presumably, in the modern dactylic form). He finally found the perfect title. But these doodles show that, like

most of us, Kubrick was human before he reached for

superhumanity. My favourite gleaning from this exhibit is the exchange of thoughts

between Kubrick and Karl Wittgenstein. You must

gather the opposing quotes from different rooms, since the organisers obviously

didn’t realise how one declaration was Yin to the other’s Yang. But where Kubrick is commemorated in a wall-quote as saying “If it

can be written or thought, it can be filmed,” Wittgenstein is quoted, in a

letter from an academic writing to Kubrick to rave

about DR STRANGELOVE, as saying, “What is done cannot be said.” Doesn’t that contradiction define the movies? Doesn’t it give us

cinema in a nutshell? Vast volumes of thought and research and annotation and homework and

accounting and calculation and preparation precede the making of a movie, or

at least of a Kubrick movie. Yet the work itself,

once done, is irreducible. It cannot be unmade again into words and figures.

It cannot lose what has made it, at a stroke, transcendental. It is sorcery,

it is magic, in the form of sounding pictures and moving images. COURTESY T.P. MOVIE NEWS. WITH THANKS TO THE

AMERICAN FILM INSTITUTE FOR THEIR CONTINUING INTEREST IN WORLD CINEMA. ©HARLAN

KENNEDY. All rights reserved. |

|