|

. |

|||

|

AMERICAN CINEMA PAPERS

|

A NOBLE MIND HARLAN KENNEDY 1935-2022 By Nigel Andrews

He was a wonderful, even at times a great film critic. He was my close friend for 50 years. And I mourn his death more than I have mourned anyone’s outside my own family. He was a warm companion, an unsurpassable wit, a man of impassioned curiosity and intelligence, and a mind so frolicsome you had to love it; though a few grudging souls opted not to love it, I remember, in those earnestly shuffling airplane-boarding queues where Harlan might suddenly, heedlessly, obliviously break into song with a medley of Broadway show tunes or torchy pop ballads.

He was the founder and the single, sovereign voice of American Cinema Papers for some 30 years: that rich mix – this rich mix - of essays, reviews, interviews, profiles, festival reports, which I seem to remember began, like all great things, as an idea over lunch or coffee. Probably when we were in some remote festival location, decades ago.

I know how proud he was of this, his site devoted to cinema of the world and cinema of all time. I know it was his most cherished achievement as a film lover, even though he had held writing and editing posts on two flagship magazines devoted to American cinema, ‘Film Comment’ and ‘American Film’, and had also written for publications from the New York Times to Vogue.

As a film fan he knew almost every line of every movie – or every movie which had rung his bell and tolled its way into his pantheon. (Start with THE BLUE ANGEL, proceed to CASABLANCA, continue to ALL ABOUT EVE, add a coda with AS GOOD AS IT GETS. And that’s just the lighter side of his taste).

But the classic line which came to me when I heard of Harlan’s death was not from a film but from a play. “Oh what a noble mind is here o’erthrown,” says Queen Gertrude of her son Hamlet. She’s referring to her son’s reason, not his life or being. But who would not say, of Harlan, that his mind was his being? Or the summit of it. And the ‘summa.’ And – let’s pun on - the summer too. There were few days in his company, or few hours blessed by his conversation, where the sun didn’t shine and the birds sing.

That summer is sadly over. But the line from HAMLET has another sadness too. Harlan fell victim to dementia, or a form of it, in his last year or two. That’s why a silence fell over American Cinema Papers. And that’s why memories of him, for surviving friends, are keener and more acute than for a simple single death. This was a twofold dying. First the Aladdin’s cave of the Harlan mind and spirit, once so measureless and glittering, was emptied of its treasures. Then the cave itself was closed and sealed.

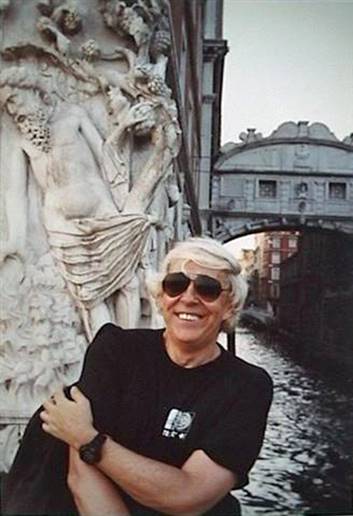

What treasures those were, though. He lived in London and several times we motored down to the Cannes or Venice festivals together, me in the driver’s seat, he in the passenger’s. The entertainment was non-stop. It wasn’t just his tunes and songs: he was a one-man Spotify, I knew that. But he could also riff and ad-lib entire free-form, free-association monologues, like an expert stand-up comic, from a single word, phrase or idea.

Once, while driving south from the Venice festival to our favourite hotel in Rimini (Fellini’s birthplace), he extemporised on a couple of lines from a Diana Ross song, possibly heard on the car radio. He built them into an extended, structured, hilarious improv – scat and scatty – composed of bluesy pretension, bebop philosophy and soapbox metaphysics, larded with high-octane schmaltziness and big-band grandiloquence. You had to be there. It lasted about ten minutes. It was hysterical. Happily I was there; then and often.

In a public space he had the knack of catching eyes. At the Berlin Film Festival, the actor Oliver Platt delivered a fulsome, slightly kidding introduction to a movie he was starring in. We all applauded, Harlan a shade more flamboyantly than most. As he walked up the aisle, Platt looked at him and said – kiddingness intact – “Nice speech, huh?” Harlan loved that. Other things apart, it was so close to what Bette Davis says, acidulously, to Anne Baxter after Baxter’s cooing award-acceptance speech at the start of ALL ABOUT EVE. “Nii-ce sp-eech, Ee-ve”. Or words to that Bette-ish effect.

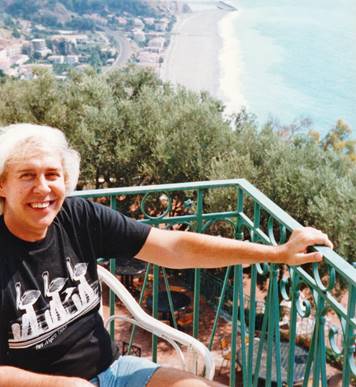

I remember too a lunch for half a dozen English-speaking critics at the Taormina Film Festival where the guest of honour was bygone Hollywood star Dana Andrews. A film noir heartthrob in the 1940s and 50s, Andrews had turned into a dapper-grey supernova of seventy-something. He spoke (but then he always did) as if he had just swished down half a dozen cocktails. The enchanted baritone slur, with its portamento modulations, held us spellbound. I remember that Harlan alone, among us awed fans, was cool enough, contained enough, perhaps mischievous enough, to ask questions that actually tested Andrews – and that provoked coherent, diligently wrought, interesting answers.

I loved Harlan’s writing. As an essayist, reviewer and reporter he wrote like nobody else. Reading some cinephile magazines, I can’t tell one word-boffin writer from another as they tune into the usual film-buzz argot and invoke the usual film-buzz thought masters. (The decade of Derrida. When was that? Semiology and structuralism. When were they at their scary height?) But Harlan wrote as if he loved writing, plus he loved film, plus he loved taking the mickey, sometimes, and spoofing the whole ceremonial of movie criticism.

Didn’t he once interview King Kong? (Yes, he did. In a contribution one year to the Berlin Film Festival magazine). Didn’t he once write an appreciation of BARRY LYNDON, Kubrick’s great living movie-tapestry based on W M Thackeray’s novel, that was couched entirely in 19th century Thackerayan prose? Unerring 19th century Thackerayan prose.

Yet he could also deep-dive intellectually. He wrote an intricate and wonderfully persuasive piece on the kinship – or sets of kinships – between THE THIRD MAN and TOUCH OF EVIL. Uncanny correspondences were explored in two films previously twinned, in people’s minds, only by their noir atmospherics and the starring presence of Orson Welles.

My favourite, though, of his longer thought-pieces for American Cinema Papers is ‘The Time Machine’. He’s the only critic I’ve ever read who captured in a single long essay the queasy, disturbing nature of what cinema actually is. It’s a machine for denying age and death in the cause of keeping stars, and perhaps directors too, eternally young. It’s a ‘picture of Dorian Gray’ that holds the blessed and the chosen ever fresh and youthful for us, while we mortals moulder in the audience seats, staying alive with hope and popcorn.

Into the arms of this embracing theme, Harlan pushed everything from horror films to the theme and meaning of camp to the great masterworks like CITIZEN KANE and METROPOLIS.

He had another quality. He could make everyone like him. He was a natural as an interviewer – and, rarer art, as an interview getter. Famous people, unsurprisingly, can be resistant and elusive. I was with him on a trip to Prague in the Czech Republic where Steven Soderbergh was making his eagerly awaited second feature film KAFKA. (Okay, it bombed. But it had its fans, including wunderkind German director Wim Wenders). Jeremy Irons the star, we were told, who had just won the Best Actor Oscar for REVERSAL OF FORTUNE, was giving absolutely no press interviews. Harlan, beguiling Harlan, was in his trailer within an hour. The interview was published in American Film magazine.

Talking of German wunderkinder, I was also with Harlan when he gatecrashed – no other word suits – the strictly-no-press location for Werner Herzog’s NOSFERATU THE VAMPYRE. We were in Delft, Holland, he on assignment for American Film magazine. Harlan tagged me along to a town council meeting at which Herzog was trying to persuade the Dutch elders to let him release a few thousand rats through the streets. (That story, with Harlan’s byline and Herzog’s consent, went into the New York Times).

Herzog took an instant shine to us. Or to him. Harlan was soon slumming it and chumming it with the film team, sharing meals with them in the barely furnished apartment house (which had been a Gestapo HQ during the Occupation!) where they were staying. Even Isabelle Adjani, then a big star, had gone low-rent and bohemian and was a member of the commune.

The exception among the cast was Nosferatu himself. German star Klaus Kinski, playing the vampire, had opted for the luxurious seclusion of the Rotterdam Hilton. Once we knew this, Harlan and I drove out of Holland via Rotterdam, on the faintly ridiculous off-chance that we would catch the journalist-hating Kinski unawares.

We did exactly that. Beyond-ridiculously, we sighted the actor’s shaven pate through the window of the Hilton restaurant whilst driving past. Harlan went in, introduced himself and charmed the pants off Kinski. Kinski returned the favour by charming the pants off Harlan. A successful debriefing in all senses.

I remember only one occasion when his charm failed. It involved Vincent Price. I was in Hollywood obtaining interviews for BBC Radio. Harlan, with his own assignments, was at the same hotel. This was a Saturday and I had booked to meet Price at his house the next day, Sunday. On this day I was driving out of town for another interview. I got back late to Los Angeles to find – guess what.

Price had got the date and place wrong and had turned up that afternoon at the hotel. The management had notified Harlan, knowing we were buddies. Harlan came down to the bar. He ‘recognized’ the wrong person and overlooked the elderly, actual Vincent Price sitting in the corner wearing, Harlan later told me, moon shoes. The wrongly identified person protested his innocence of any connection with the star of HOUSE OF WAX and THE FALL OF THE HOUSE OF USHER. The said real star walked out, protesting to the management with (Harlan said) a Vincent Price-ish wail that “he didn’t even recognize me”.

I got the same line from Price when I phoned him later. I appeased him, pacified him and made a new date. A clever friend had thought up the idea of my telling Price that Harlan knew nothing about movies, being the BBC’s Religious Affairs Correspondent. You had to know Harlan to love the lunacy of that. A modern Lloyd Bentsen would surely have accosted him with: “I know religious affairs correspondents. Religious affairs correspondents are friends of mine. And you, sir, are no religious affairs correspondent”.

It’s a cliché and hyperbole to say that the death of someone – however dear or celebrated – is the end of an era. But for me Harlan’s death was that. He made filmgoing and film reviewing and film conversation such fun, such fantastic fun. Fun is the word I can’t stop using. He had no time for cant or pomposity, for cultural words-of-the-day, jargons-of-the-month or flavours-of-the-year. As a writer he went out there like a busker and did his stuff. And often it was original, startling, impudent, chatty, parodic, revelatory, or effortlessly intuitive.

He loved Pauline Kael, of course. The longtime New Yorker film critic was another street busker with a brilliant mind. And like her, Harlan had his quirky, sometimes crazy-seeming favourites among films and directors.

He never stopped loving HEAVEN’S GATE, for instance. For all the spendthrift, monomaniacal, overambitious, studio-impoverishing hubris of Michael Cimino’s film, he saw that there was something dedicated, radical and wondrous about this epic-sized re-reading of the western.

He was among those who lobbied for a showing of the nearly-5-hour full version of the movie at London’s National Film Theatre. This was a work completely different – sensationally different - from the truncated travesty put out to early reviewers when the film premiered in America (with the consent of a browbeaten Cimino). Those reviewers duly damned it.

Cimino was there in the London audience, weeping, when the film was acclaimed and long and loudly applauded. Recognition, finally served.

Sometimes critics aren’t just parasites on the body cinematic - their probing pejoratives at the ready, their pens poised to suck the life from an embattled art and entertainment form. That’s the way critics can be popularly perceived. I know. I have been one.

But sometimes critics love cinema and will go to the wall or the world’s ends for it. When they adore a movie they’ll shout about it and, in Harlan’s case, probably sing about it. They’ll campaign, they’ll champion. And even when they hate a movie, they’ll do it with a breadth and depth that includes the good they find missing – because invoking the good and great is always a benefaction to readers - and not with a carping that is parochial, pedantic, self-serving.

I shall miss him. I think many will miss him.

Harlan himself would probably want to be remembered with nothing more than a shrug and a simple, acknowledging word. He loved – what filmgoer doesn’t? - the laconic epitaph Marlene Dietrich gives Orson Welles at the end of TOUCH OF EVIL. “He was some kind of a man.” Pause to peer into the indifferent, engulfing darkness. “What does it matter what you say about people?....”

_________________ [1] Nigel Andrews lives in London, England. He was film critic for the Financial Times newspaper from 1973 to 2019.

|

|

|

|

|

|

||