|

. |

|||

|

AMERICAN CINEMA PAPERS

2011

|

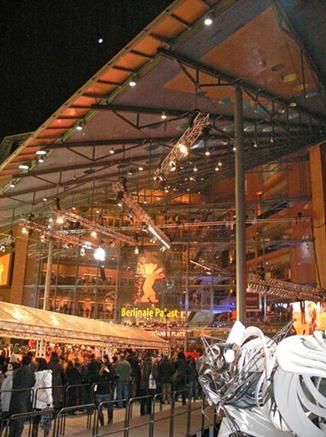

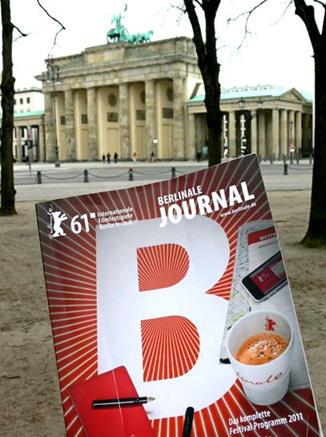

BERLIN FILM FESTIVAL—2011 MASTERLY ADMONITIONS by Harlan Kennedy Infernal investigations! The Berlin Filmfestspiele

has been good at these for decades. So good we almost take its ministrations

for granted. Shining a torch into the hellish, heinous and horrendous, as a

movie arena it has learned from experience. A city once cracked in two, whose

crack extended upwards to the sky, knows about schism and disunity. A city

once host to history’s most hated man, whose bunker is a tourist stopover,

knows about the inhumanities humans can devise for each other. So two films jump out at Berlin, perfect,

terrible and dazzling. Masterly in their admonitions to us, to everyone and

to all who come after. Bela Tarr’s

THE TURIN HORSE is from the stables of the apocalypse. The Hungarian

filmmaker derided by some for crafting works of torturous minimalism

(SATANTANGO, WERCKMEISTER HARMONIES) – and loved by others for the same

reason – states this will be his last film. How apt that it shares a festival

with an Ingmar Bergman retrospective. Like Bergman, Tarr’s

greeting to his audience is always: “Are you sitting comfortably? Then we’ll soon

deal with that.” Ralph Fiennes’s CORIOLANUS is stupendous

screen Shakespeare. The actor turned actor-director turns a notoriously

‘difficult’ play upside down, shaking it for the gleam of loose change. It

really does seem as if the Bard set

his play in the 21st century Balkans,

where Fiennes and team – working out of Belgrade – make their Roman hero live

again. And die, slain by his refusal to play the Realpolitik game. This play about honour and dishonour, about integrity

and time-serving, is so modern it can hurt. Here it does. Both movies have the impact of turning

over a stone and discovering a portal to hell. Not just worms and

creepy-crawlies, but a shaft, a tunnel, to the worst inferno there is. Bela Tarr

is keen on Satan. And in a way on God. The forces of woe in THE TURIN HORSE

appear to be of the Devil’s and the Deity’s combined making – always a good

team when persuaded, like a rock group, to get back together again. But Tarr, though mystically inclined, has the time and vision

to fault mankind. Human beings are as much the problem for him,

and perhaps the solution if they would only knuckle down. Nature is a foe too and, handed the

opportunity, will give nurture a good drubbing. Then there’s Nietzsche, who

engenders the film’s source anecdote overvoiced in

the prologue, in which the Turin-dwelling philosopher embraces, sobbing with

seeming sympathy, a recalcitrant cab horse in the street outside his home.

(True story). Nietzsche, we are told, spent the rest of his life in a

mysterious torpor, writing no further works. Is the horse in the movie that horse? Who knows.

We are told nothing, we are just shown. In a tremendous opening sequence we

see the mare towing her cart, straining against mist and wind to carry her

bearded, whitehaired master back to his

smallholding in a blasted, howling plain. We see the daily ritual whereby the

daughter dresses and feeds the father (one boiled potato each, in a wooden

bowl), helps him harness and feed the horse, fetches water from a well made almost unreachable by the violent wind,

undresses the father for bed…… It’s all in black and white, like a

commercial for despair. Or a plea for the final (dis)solution. The horse goes

off his food, the wind lays ever fiercer siege, the

bottle of palinka (a stomach-firing liqueur)

dwindles to dregs. Over the 150 minutes or five days of story time the

dwelling is taken over by a kind of slow-motion chaos, a spiral of doom.

Halfway through, a cartful of gypsies visit in a macabre vignette, rowdying at the well and stealing water. (The well dries

up the following day). One gypsy leaves the daughter a book full of

crypto-scriptural warnings. The film’s trajectory is surely a reverse

Creation: a progress towards no-life and even, in the last scene, no-light.

Instead of “lux fiat”, “nox fiat.” Sin and

transgress enough (Tarr seems to say) – and who

knows what covert biblical misdeeds this mysterious parent-child couple have

committed? – and God and providence will blacken the

world. Either that or providence does it all itself, with no need for moral

justification and no credit for an omniscient judgment call. That’s a comfort for unbelievers. They

like to believe the world can do its own self-destruction. Enact its own back-to-front Genesis. Reverse creation? Style

fits subject. Visually and aurally THE TURIN HORSE reinvents the wheel. It

even uninvents it, restoring us to a primitivism where the still image barely

reaches out to other images to spark the miracle of Persistence of Vision.

It’s a film of blazing stasis, dazzling inertia. It exercises a choke-hold on

the viewer, who can’t and won’t escape. This kind of incarceration is too

good not to endure and enjoy.

CORIOLANUS takes us forwards, not

backwards. Instead of uninventing the wheel, it fast-speeds us towards a

modern inferno. Rome and Antium, though keeping

their names, are in Serbo-Croatia. Costumes are

today’s battle fatigues. TV newscasts blurt about a “Roman food crisis” and a

“Volscian border dispute.” The titular Tiberside general – played by shaven-pated Fiennes with a

ferocity he hasn’t shown since SCHINDLER’S LIST – conquers Volscian leader Aufidius

(Gerard Butler). But victory is followed by a leadership election in which

Coriolanus refuses to bare his wounds (ancient Roman equivalent of kissing

babies). He storms from his city, damning its rejecting citizens. The new

ally for revenge, for re-invasion is who but Aufidius? This is the Shakespeare who wrote about

spin and pressing-the-flesh, about Realpolitik

and reality electioneering, centuries before those concepts became

commonplace. By modernising the play – and hiring HURT LOCKER’s Barry Ackroyd as cinematographer – Fiennes reminds us of its

eternal topicality. We even see a hint of THE MANCHURIAN CANDIDATE in the

hero’s manipulating mother Volumnia. Vanessa

Redgrave plays her as a kind of living human effigy, dry, gaunt, tindery, constantly re-ignited by her passion for power.

She goads her son to compromise his principles to attain high office. When

that fails, she chases him to the border on his armed return to beseech him,

in a blaze of eloquence, to relinquish his vow of vengeance. Where better than Berlin for this

CORIOLANUS to be premiered? Here its key line, “What

is the city but its people?” has a defining acoustic. For so long Berlin was

everything but the people: a

monstrous, mutating plaything of its civic masters. Now the will of the

people has triumphed; it is their

city. They have terraformed the political desert.

They have banished the monsters of right, then left, who thrived in its

barren byways and highways. Both these movies are warnings as well as

celebrations. Warnings that chaos can come again and so can confinement. The

invisible wall of warring elements that encircle Bela

Tarr’s characters belongs in this city of freedom

that was once a jail. Or worse: a jail that looked out across a divide at the

mocking pageant of freedom occupying the other half of the city and, beyond,

the other half of the world. In CORIOLANUS the atavistic threat of old

aggressions, old spites, returning to their native city holds up its warning. An ancient Rome (even if

disguised on screen as a modern Serbo-Croatia)

speaks to a remade Berlin beset at times by all the old bigotries, the old

ethnic hatreds. Time never sits still, even though it playacts doing so in

THE TURIN HORSE. The words “never again” are too often the preface to the

next apocalypse. They should be uttered only as a prayer, never as a certitude. COURTESY T.P. MOVIE NEWS. WITH THANKS TO THE AMERICAN FILM INSTITUTE FOR THEIR

CONTINUING INTEREST IN WORLD CINEMA. ©HARLAN

KENNEDY. All rights reserved |

|

|

|

|

|

||